Producing a dictionary of the Chorasmian language has been a goal within Iranian philology for about seven decades. Two major figures in the field, Henning and MacKenzie, dedicated a significant part of their careers to that goal—and both were unable to finish their work or make much available to the public before their deaths. Fortunately, the materials left behind by both scholars provide a solid foundation to attain this goal, indeed, perhaps even all the necessary building blocks. In this post, I aim in the first part to overview these existing materials and in the second to discuss the approach to compiling and organizing them to produce an online and accessible dictionary of Chorasmian.

Part 1: Existing unpublished sources

To compile a (non-etymological) dictionary, the following materials are the primary foundation:

- A draft printout of completed entries ʾ- through γw-, almost 1900 entries together with a slightly older version of the corresponding digital file (MacKenzie)

- An older and less complete draft entries of ʾ- through n- on paper (MacKenzie)

- Printed and digital versions of the concordance of the entire lexicon, organized alphabetically (MacKenzie)

- Computer files containing the Chorasmian words and phrases in each source text (MacKenzie)

- Handwritten index cards of the entire lexicon (MacKenzie, Henning)

The most recent work seems to be the print-out of ʾ– through γw-, probably dating to mid-2001 a few months before MacKenzie’s death. His computer file for ʾ– through γwxy– is very slightly different than the print-out, mostly in the format of lemmas, and seems to be a slightly older version. This draft of almost the whole of alif through ghayn, about 1900 completed entries, is essentially complete and can be used verbatim as the basis for the dictionary (but will be reformatted, see below). These probably constitute 30-40% of the entire dictionary, especially given that such a disproportionate number of forms begin with alif (almost 1,000!).

From γw– to the end of the alphabet, dictionary entries will have to be created. But this job is much easier because MacKenzie had already gathered and arranged all the attestations in the form of multiple concordances, so it is ‘simply’ a matter of writing the entries, arranging the existing phrases listed in the concordance, and adding the appropriate grammatical information. My impression of the concordances is that they are essentially complete, and this will save the very time-consuming work of gathering up attestations of words for the dictionary entries.

In addition, previously published works can be compared to verify readings and conjectures, such as Benzing’s study of the Muqaddima plus MacKenzie’s reviews, and MacKenzie’s edition and glossary of the Qunya. Note that Henning’s incomplete dictionary draft was already published, and absorbed into MacKenzie’s more extensive materials, and so does not really figure into the compilation of the dictionary now.

For etymologies, the work will be based mainly on various published materials, especially those of MacKenzie (and including his unpublished lists of etymologies for the dictionary entries of alif and ba only) but also using a much wider selection of Iranian philological works up to the present day. Adding etymologies to the entries will be a secondary task, to be taken on after the bulk of the entries have already been produced. It will require not only gathering etymologies for Chorasmian words that have been proposed in the literature, but evaluating them and proposing new ones with a critical historical-linguistic and philological eye.

It should be noted that the above materials, and the compilation of a dictionary thus far, only includes later Chorasmian—that is, the form of the language represented in Arabic script dating to after 1000 CE. But what about Middle Chorasmian?

Middle Chorasmian, the form of the language attested in its own script and largely from pre-Islamic times, should ultimately also be included in a comprehensive dictionary, but this involves two major problems: 1) the majority of Middle Chorasmian texts are not published or even deciphered, and 2) they are written in a different script, based on Aramaic and using Aramaic heterograms. The words attested in the published, deciphered texts could be included in the dictionary at a later stage, perhaps under a headword with hypothetical transcription so as to align with the later Chorasmian data, but this partial solution does not seem satisfactory. Once more texts are available, a separate (and much smaller!) Middle Chorasmian lexicon is perhaps doable and will fall within the scope of the present project. Another approach might be to include only the Middle Chorasmian words for which later Chorasmian equivalents are attested.

Part 2: Methods

The most efficient way to produce a Chorasmian dictionary based on the materials we have would probably be to just reproduce MacKenzie’s entries verbatim and then move on to producing the remaining entries. But, I don’t really want to do it this way—the main reason being that I find the format of MacKenzie’s entries to be rather difficult to read.

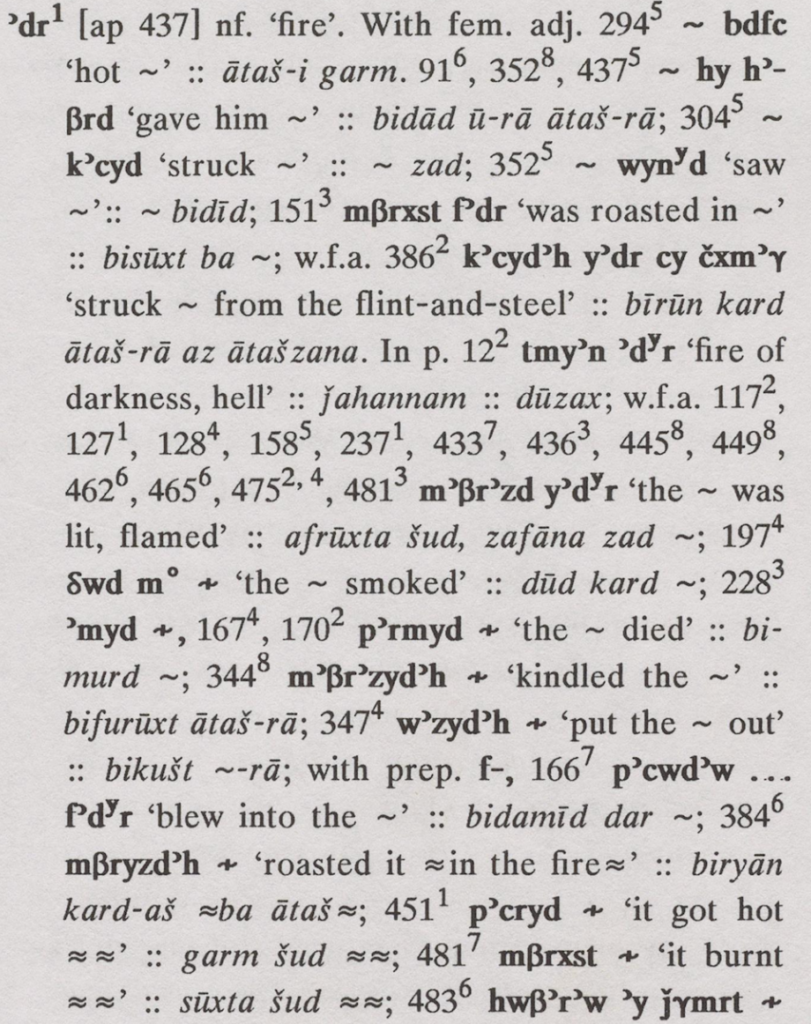

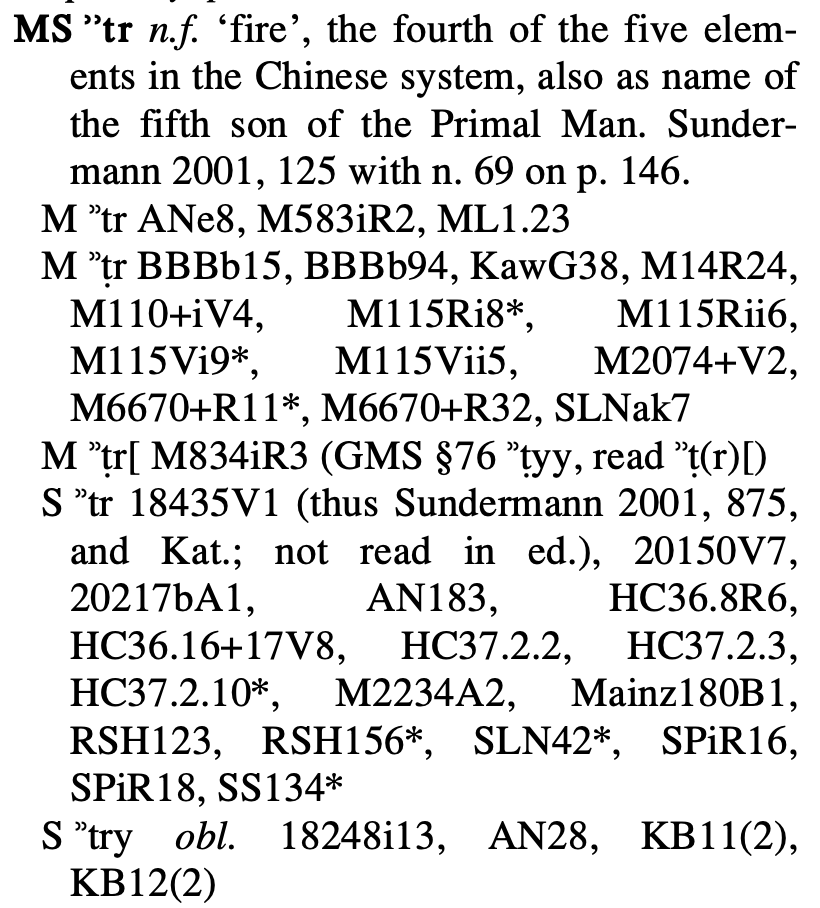

Here is a fairly simple completed entry, for ʾdr ‘fire’ (the last line continues on the following page, which I didn’t manage to include in extracting the image):

The text of the entry is not organized totally randomly, but it is not presented in a way that facilitates locating forms of the word ʾdr. You have to really strain your eyes to find that ʾdyr is how the word looks in pause or that fʾdyr is how it looks in pause but with the prefixed preposition f– ‘in’. And then, you have to keep in mind all the abbreviations: p. is for ‘pause’ not ‘page’, w.f.a. means ‘with feminine adjective’, and so forth. I would prefer to organize each entry by word-form to facilitate browsing—and finding—the particular form one might be interested in. (I also find the boldface for Chorasmian unnecessary.)

And then, there are all these mathematical symbols, the function of which is to save space on the printed page: the proportion sign ∷ indicates that the following text in Persian and/or Arabic is the equivalent for the Chorasmian word or phrase; the almost equals sign ≈ is for the repetition of the most-recently quoted phrase in Chorasmian, its Persian or Arabic gloss, or its English translation; the tilde ∼ shows the place of the lemme itself in a phrase or translation, while finally the ‘not tilde’ ≁ stands for the last quoted variant form of the lemma. As far as I’m aware, standard dictionary practice mostly makes use of the tilde but not the other signs. As a reader, I find it cumbersome and tiring to have to figure out—for every single entry!—what exact phrase or form is being referred to by means of the ≈, ∼, or ≁. One can understand the reasoning, which is that it seems important to show the context for each attestation of a Chorasmian word; this improves and facilitates understanding of usage and stays true to how Chorasmian words are preserved in a multilingual glossing context. This approach differentiates a dictionary of Chorasmian from, say, the existing dictionaries of Sogdian. But concerns about space on the printed page are not relevant to the current project, and I would prefer simply to make everything easier to read. So, we are going to remove most of the symbols.

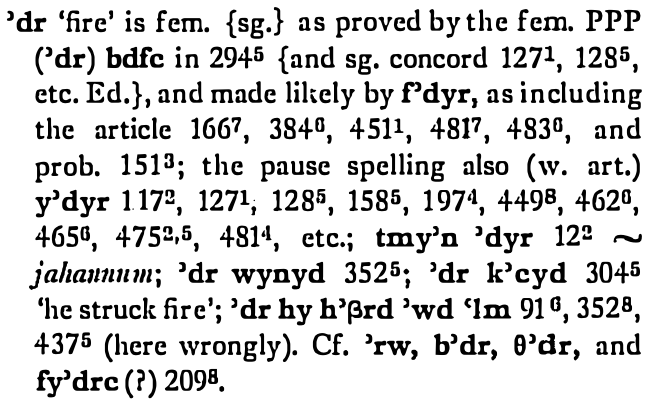

A quick aside: the format of these entries has part of its origin in Henning’s arrangement, which was more of a ‘narrative’ arrangement dealing with the attested forms (and in many cases needing to prove grammatical analysis) than a listing, as can be seen in the image on the left.

To give a demonstration of what I would prefer to do with each entry (increasing the amount of work for the sake of ease of use!), here is an example using ʾdr.

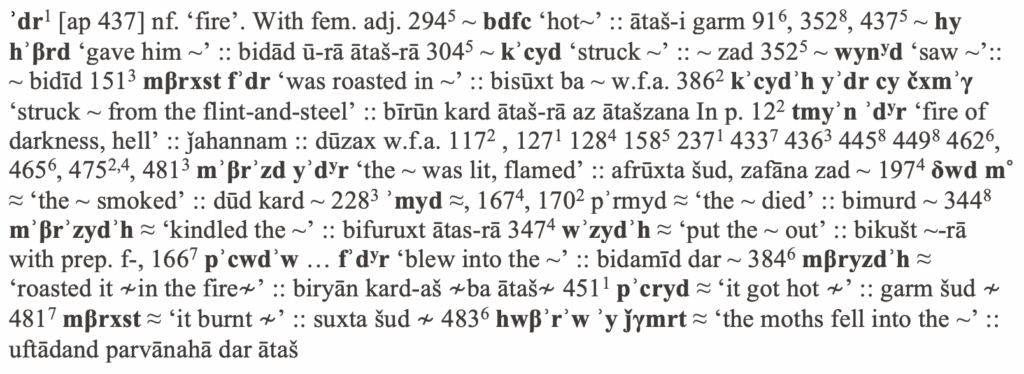

If MacKenzie’s entry looks like this (as converted into a text document):

My reformatting and re-arranging of the entry—with the etymology and cognates thrown in for good measure!—looks as follows (click here for the “beta” version of this entry currently online):

For me, this makes it far easier to see what forms fall under a given lemma and to see the full context in which they occur without making an inadvertent error of substituting the wrong form into a phrase. The brief explanation of the word-forms is also explained clearly rather than relying on abbreviations. After the cited word-form, such as fʾdr, a citation for where it is attested follows (Muqaddima, page 151, line 3) and then the complete text of the phrase in which it occurs (mβrxst fʾdr), with the corresponding gloss (here, Persian bisūxt ba ātaš). Another benefit is that this arrangement is somewhat easier to encode in XML/HTML than maintaining the particularities of MacKenzie’s format.

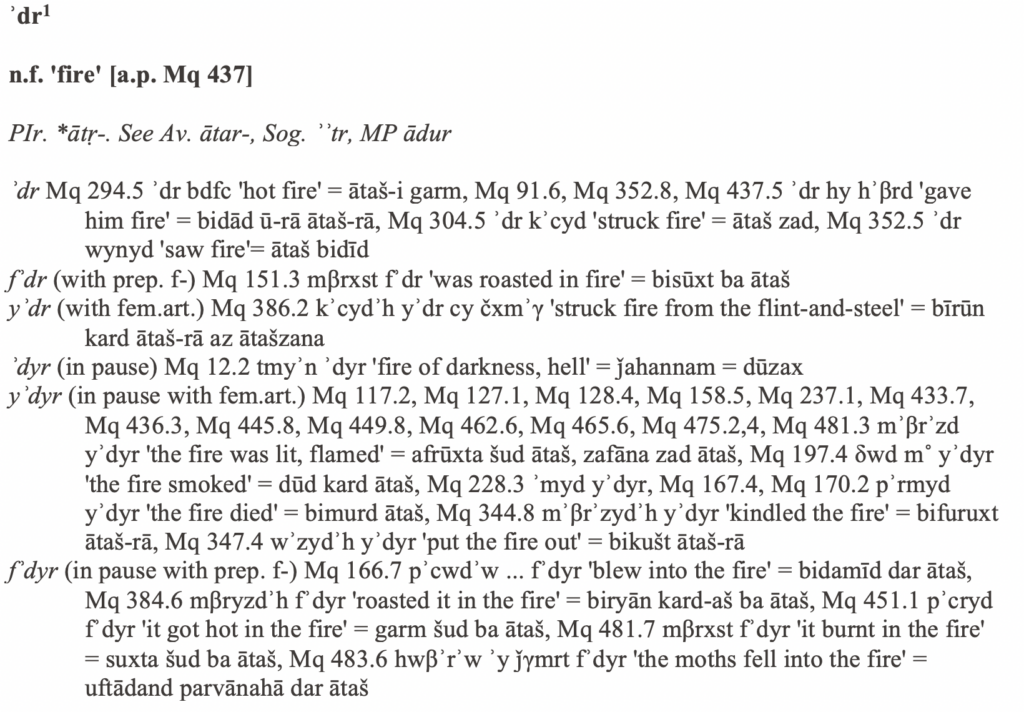

Moreover, this brings the format of each entry in line with dictionaries of related languages that someone might be consulting, such as the Sogdian volume of the Dictionary of Manichaean Texts. Here is a sample from that:

Obviously, the Sogdian dictionary shown above provides only a listing of manuscript/page/line on which the given form occurs; for the context, one has to track down the corresponding publication (provided in a key at the beginning of the dictionary). This is a complexity of the Sogdian which the Chorasmian doesn’t have, since we are dealing for the latter with essentially four texts preserved in maybe a dozen separate manuscripts.

The last step in finalizing an entry is encoding it in a format which can be fairly easily presented online. I am doing this using the ORACC platform (see the “beta” version of the dictionary here) with the generous assistance of those colleagues. How Chorasmian dictionary entries are being encoded will be the subject of the next blogpost in this series.

I would be interested in hearing what others think about the reformatted version of MacKenzie’s dictionary entries. Is it indeed easier to read? Are there changes you would suggest? Please feel free to get in touch.