The Persian dictionary Burhān-i Qāṭiʿ, compiled by Muḥammad Ḥusayn b. Khalaf al-Tabrīzī in 1062/1651-2 in Ḥaydarābād, mentions the use of two very particular terms in the language of the town of Khivaq in Khwarizm (ed. Muḥammad Muʿīn (Tehran, 1330-5 s./1951-6), Vol. II, 1183, also available here):

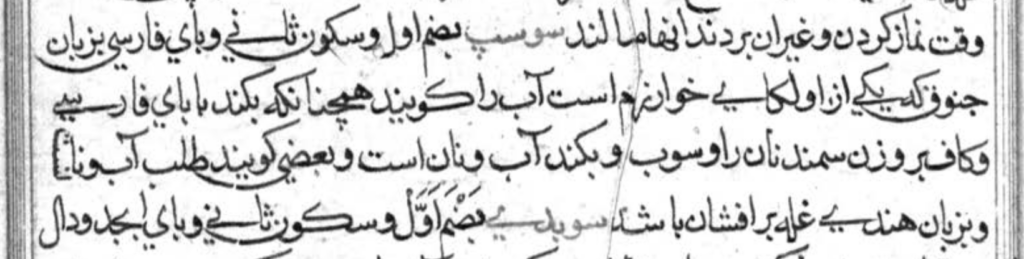

سوپ - به ضم اول و سكون ثانى و باى فارسى به زبان خيوق كه يكى از الكاى خوارزم است آب را گويند همچنان كه پكند با باى فارسى و كاف بر وزن سمند نان را و سوپ و پكند آب و نان است

sūp, with ḍamm on the first (letter) and sukūn on the second and a Persian 'b', in the language of Khivaq, which is one of the provinces of Khwarezm, they call “water” so, just as they call “bread” pakand. So sūp o pakand is 'water and bread'.

Khivaq (modern Khiva) was one of the areas constituting medieval Khwarizm, and as it may be assumed that Chorasmian was spoken there during its heyday, we might assume these words cited by the Burhān to be Chorasmian. But a quick comparison with the known Chorasmian sources doesn’t completely confirm this. The more straightforward of the two is pknd, which is mentioned in all the important Chorasmian sources (It’s worth also remarking that much earlier than the Burhān, and even most Chorasmian sources, Ibn Faḍlān (mid-10th cent.) also mentions pknd for Chorasmia). But it is unusual as an Iranian term for bread, the more common being some form of what resulted in Persian نان. Harmatta (1953, 270ff.) derived pknd from *upa-kanta- ‘(bread) dug or covered (in ashes)’ i.e. ‘bread baked in ashes’, which MacKenzie (1990) seems to agree with in his edition of the Qunya. From the root *kan would also come the Armenian form nkan, belying an Iranian *ni-kāna- meaning ‘bread baked in ashes’ as well. (All other ‘bread’ forms in Iranian languages, such as Sogdian nγn and of course Persian nān, would derive, thus Harmatta, from an unrelated *naγna-).

The Chorasmian word for ‘water’ is cwb, which is less clear. The Burhān’s sūp, though, is simply Turkic: Maḥmūd al-Kashgari, in his famous 11th-century dictionary Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, records süp for ‘water’, and forms with final voiced fricative sūv are also known. The form cwb recorded in the Chorasmian sources several centuries before the Burhān, might be held to reflect a Turkic form in some way. MacKenzie argued that it represents an accommodation of an original Iranian *čāb to the Turkic sūv or süp, with *čāb deriving from *usačā-āpah (MacKenzie rejects as nonsensical Freiman’s suggestion (1951, 103) that cwb is equivalent to New Persian ǰūb ‘canal’, derived from *yauwiyā- + āb ‘water’). But one wonders if there is any reason to reconstruct a more complicated etymon for something as simple as ‘water’ than most other Iranian languages have (usually just a reflex of *āpah-), especially when there is a Turkic word available which conforms more nicely to the shape. While Turkic loans are not numerous in the Chorasmian materials, it is evident that they have absorbed words from a number of languages and, in addition, mention the presence of Turkic. However, the initial affricate [ts] of the Chorasmian form is hard to explain if the word is simply a borrowing of süp, since Chorasmian could easily have rendered it with initial [s].

The 17th century CE is very late for Chorasmian, even though the manuscripts thought to have been copied by people who did not necessarily speak Chorasmian precede that date by only a century or two. Perhaps in rural areas a version of the language did survive for some time. Or perhaps, a few special words, of ultimately Chorasmian origin, survived as a local Khivaq-ian flavor in a landscape of Persian and Turkic dialects.